Fight Back with the Claimants Union! From the MayDay Rooms Archive.

By Georgia Anderson and Cathy Leech for Mayday Rooms. Image: Mayday Rooms

Have you ever been on the dole? What’s changed in the past thirty years in the ways unemployed, sick or disabled people go about claiming money from the state? Certainly, there’s been a material shift from analogue to digital; standing in dole queues with a flimsy newspaper-thin logbook, to online courses for writing CVs and emails forcing you to read a message in your ‘journal’ lest you be sanctioned. The generation of people now receiving Universal Credit might be amazed to know that there once was a mass movement of ‘unionised’ benefits claimants who met up regularly to discuss their claims. Have you ever thought about how people claiming benefits find out information about their rights to benefits? About the multiple ways in which the job centre try and punish or trip you up? Nowadays when you go you are unlikely to regularly see anyone else in your local area. Perhaps they know that if people connect with someone over this shared experience, they might start sharing information, organising and resisting the system like people did in the 1970s and ‘80s when they started the Claimants Union movement.

Information about how benefits like Universal Credit and PiP are allocated is spread mostly via hearsay and scaremongering. The digital all-seeing-eye keeps people fearful of whether the DWP are able to check bank statements, and the repeated messages about fraud make you feel like a criminal every time you have an appointment booked. But just try to imagine a time before the internet, back to 1969 when the first Claimants Union was founded in Birmingham by a group of five young people from working-class backgrounds. They all had direct personal experience of claiming and got together to demand their right to a decent income through collective action. They began by leafleting other claimants outside their local job centre.

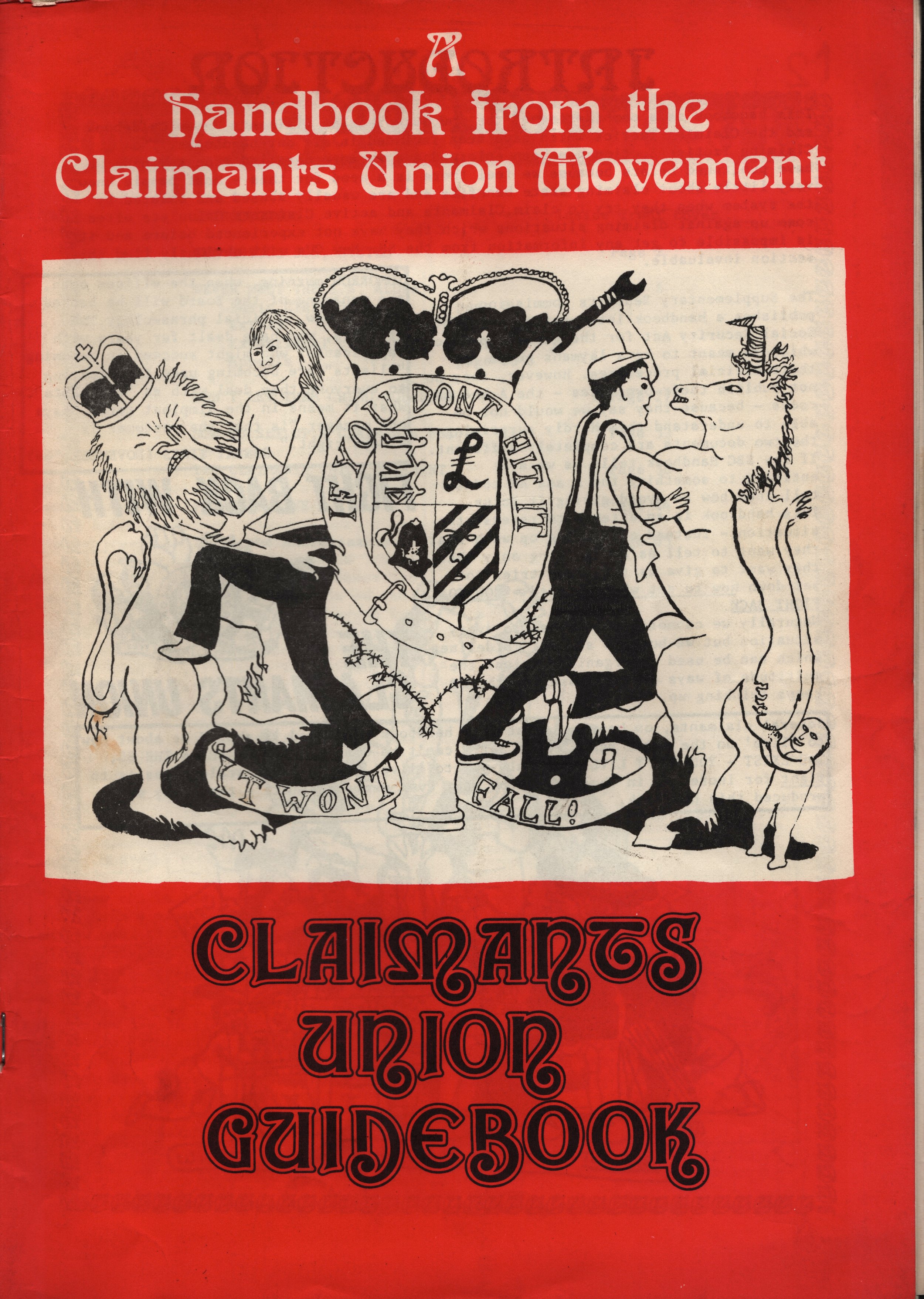

Before 2001, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) was called the Department for Health and Social Security (DHSS), and they have always relied on claimants not knowing what they could claim for. This gives them the power to reduce payments seemingly at whim and keep the power firmly on the side of the state. Have you ever had a good work-search ‘coach’? Rare, but they do exist! During the 1970s and ‘80s, some DHSS office workers were active in the trade union movement and sympathetic to the Claimants Unions. Through their links with these workers, the movement was able to get hold of inside information on benefit entitlements and spread it to claimants by publishing their own handbooks.

From the beginning, the demand of the movement was not just for improved treatment of claimants by the state, but the creation of a universal basic income – given as an unconditional right to all which would free the working class from ‘wage-slavery’ under the capitalist system. They had four demands:

1. The right to adequate income without means test for all.

2. A free Welfare State for all, with its services controlled by the people who use it.

3. No secrets and the right to full information.

4. No distinction made between so-called “deserving” and “undeserving” claimants.

The demand for respect and solidarity among those claiming benefits, as well as the mutual aid and sense of collective struggle against the state, was a politicising moment for members of the Claimants Movement. Groups sprang up all over the country, reaching hundreds of thousands of members by the 1980s.

From the very beginning of the movement, Claimants Unions supported their members to challenge benefits decisions at the Supplementary Benefit tribunal – the court system that claimants had to go to challenge decisions made about their cases. By 1974, Claimants Unions across the country were involved in thousands of these legal appeals a year. The goal was to win money back for the individual member while also using the cases to progress the rights of claimants as a group, either by setting precedents if they won, or by exposing bias and lack of independence of the courts, and the unfairness of the wider benefits system. Nowadays, everything is done through digital back payments, and fights won through the might of the individual who knows their rights and has the energy to appeal. “Never meet them alone” was an early Claimants Union slogan and gradually this right was won. Have you ever enlisted the help of someone who knows more than you about how the system works, and insists that you appeal a UC decision? Maybe they have even written a letter on your behalf or come with you to the meeting. That’s solidarity.

Claimants Unions across the UK remained active until around 1990. The Claimants movement grew weaker as the anti-poll tax protest movement became a new battleground of working-class rebellion. That’s another story. The growth of professional, charity-run advice centres became the alternative to Claimants Unions that partially met some claimants’ needs for support, though through a less radical, more service-based model. Following the Thatcherite years, the 1990s saw the Public Order Act of 1994, Tony Blair’s onward march toward privatisation of public services, and a shifting political and social climate. The 1990s to 2000s was a continuing onslaught of attrition on people’s sense of a right to gather and resist the state together, a struggle that continues today.

The media war on “scroungers” has never gone away and arguably, some policies toward benefits claimants introduced by successive governments in the last thirty years have been even more punitive than those Claimants Unions campaigned against in the 1970s and ’80s. Stories of carers having to pay back thousands of pounds for the DWPs own errors, and sanctions for not reading a message on an online journal, to twisted PiP advisors refusing to grant disability benefit to someone on the basis of them being ‘able enough’ to show up on time for a meeting are just a few examples of the cruel treatments endured by claimants surviving the system today. The cuts to the universal winter fuel payment for those most in need is another example of the poor absorbing another government’s punishing austerity measures while the rich and corporations continue to receive tax breaks. Where are our tax breaks? Where are our cries for universal basic income?

Radical work and the demand for better conditions do live on across the UK, with groups such as Edinburgh Coalition Against Poverty, Don’t Pay and many more. Community unions, disabled people’s and anti-austerity action groups and autonomous social centres continue to foster networks of mutual aid and solidarity to those looking for it. The global movement for universal basic income has grown – and its aims feel more urgent than ever. What would a handbook of how the system works look like now? What would meetings of claimants be like now?

By Georgia Anderson and Cathy Leech

Visit MayDay Radio to listen to some stories from original members of Claimants Unions in the 1970s and ‘80s. www.audio.maydayrooms.org/claimants-unions

MayDay Rooms Archive is running a regular feature in DOPE magazine to showcase their collection and emphasise the importance of learning from history for today’s political struggles! MayDay Rooms is an archive in central London which houses historical material linked to social struggles, resistance campaigns, experimental culture, and the expression of marginalised and oppressed groups.